My Year in 1984, 40 years ago, though an ICT Lens.

Tue, 30 Jan 2024 22:55:20 +1000

By: gosh'at'DigitalFriend.org (Steve Goschnick)

When you've been in ICT (Information and Computer Technology) as long as I have, looking back 40 years to the year 1984, is a good exercise in memory, in perceiving changes in world view, changes in one's economic and social fortunes, and giving a personal snapshot of how far the computer and software landscape has changed (and where it hasn't changed so much), since four decades ago.

I had big plans for change in 1984. I'd worked hard in the same organisation for 5 going on 6 years, with then highly desirable and rare skills of an Analyst Programmer. You could walk into your job of choice as an experienced programmer in 1984. My then wife and I had each puzzled out what we each most wanted to do in life, in the year or two ahead in particular. We had bought our own home back in 1980, had paid most of it off as fast as possible, but were not ready yet to have kids. "So, what are our biggest to-do dreams?"we asked each other. Her's was to travel to and around Europe, while mine was to start my own software company. I suggested we do her's first, as mine couldn't tolerate a big gap, midstream. Furthermore, if I was going to travel through Europe, which hadn't been a significant goal of mine at all, then we should 'Do it Big!' and go for a whole year, for the duration of 1985, to make the journey worthwhile - I was an all-in sort of person in 1984. We agreed on that, and so we set about hatching a plan to finance such a long-term trip.

Our plan hinged on saving one of our two post-tax wages and living on the other for the coming year - she was a Senior Administrator of Exams & Awards at the RMIT (e.g. she organised and ran the exams in the Melbourne Exhibition Buildings, like clockwork). While I was an Analyst Programmer in the Computer Centre at the Australian Road Research Board (ARRB). We lived on her salary and banked mine during all of 1984, to finance the year of travel in 1985! I'd started at the ARRB as a Research Assistant, in Transport research in 1979. The day-to-day tasks there turned out to be 90% programming (in Fortran77 - the Fortran language that adhered to the 1977 Standard*, note: I've retained one 'Fortran Joke' from those days … it's a good one**), and then in statistical analysis using SPSS (the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences - a product later acquired by IBM which they still have and market as their own). SPSS included a reasonable internal programming language with respect to wrangling data into the file formats needed for the data analyses that followed. My aptitude for programming became clearly abundant to others as much as to myself, and so by 1980, after publishing a couple of research papers in Transport Engineering [1,2] (for which I built a complete digital model of the transport network, including streets, of the city of Ballarat, to simulate travel-to-work times), I moved into the Computer Centre there proper, as an Analyst Programmer, doing what I really loved most - solving problems, designing solutions, and writing code.

You couldn't get a degree in Computer Science in Australia in 1979, so we Analyst/Programmers picked it up on the job, after demonstrating an aptitude to self-learn programming and then excelling at it. Although I had previously done a subject on Computer Programming within my Engineering degree, back in the second year of a four year degree - but that single subject was centred on the BASIC language, and was specifically tailored to run Finite Element Analysis programs in structural engineering. And while I did get a B+ for it, the experience ignited no passion in me for programming, whatsoever. In retrospect, I put that down to the archaic input/output workflow at Monash University back then in 1975. The Monash Computer Centre we used there then was in the Mathematics Department, and they only took punch-card input, which we students delivered to the front desk. Even small programs could amount to a 6-inch high deck of punch cards, and then you had to wait 3 hours for the printed output, of how the program compilation went! Think about that. If you had a simple syntax error, you'd have to correct that card - one line of code per card - resubmit the whole deck to the front desk of the Computer Centre, and wait another 3 hours, and so on, repeat! So doing a simple assignment could take days of stop-start frustration. It was not conducive to igniting a passion for programming. Also, the 4-year engineering degree at Monash then included 9 subjects of mathematics across those years - effectively half a three year Science degree in Mathematics alone, so that snail-slow workflow for my one-and-only programming subject, was simply a survival task amongst dozens of subjects which often became a process of: study, cram, exam and forget.

Computing at the Australian Road Research Board, even in 1979, was vastly more sophisticated than what I had access to at Monash University as a student. It was a revelation! The ARRB had a $1million mainframe, plus appropriate housing (fire-extinguishing automatic gas-filling room that housed the central machinery, and full-time Operators tending to magnetic tape loading and emptying the central printer, the 3-colour pens graphic plotter, and so on), courtesy of a Whitlam Government research infrastructure grant, some years earlier. And when I moved into the Computer Centre in 1980, the mainframe was running at about 50% capacity. Most ARRB employee (about 120) had a terminal on their desks - even the gardener, and the mechanic who kept the company carpool in check. The mainframe was a Control Data 170, which was a mean-machine in its day, with a 60-bit word design. Everyone also had email, which was unheard of in most organisations of the time. In fact, to get all staff to use email, which was essential for email to work effectively, was harder than you might think. To do so, we in the Computer Centre devised a psychological hook… There was a central Receptionist, who was the interface with the outside world - both physical visits through the front door, and phone calls through a PABX switchboard. She also took messages, each on a paper slip, which she stuck to a noticeboard (think PostIt notes, which were also invented around 1977), for those people out-to-lunch or elsewhere. I.e. that noticeboard was the social interface to the outside world, for staff in all roles, particularly when employees were off-site, or even to-and-fro-ing to the Staff Canteen, fully-catered - e.g. inexpensive hot meals 5 days a week (i.e. it wasn’t the modern IT startups that pioneered such work perks). So, we instigated a rule, that 'All personal messages coming to Reception, business and personal, would be sent to the individual's email address, instead of being plastered on the notice board, on a postit note'… That worked, and everybody in the organisation thereafter, accessed their email account regularly, and email took off within the organisation, well before it became a fixture in the outside world in general - well before the Internet and the great unwashed joined in the planet-scale dialog.

It wasn't just email that was 'modern' at the ARRB with those terminals on everyone's desk. I could create and edit my programs with fullscreen editing (in Xedit), compile and run programs in a matter of seconds, more like the modern experience, instead of that 3 hour stop-start workflow back at Monash Uni. This enlightened and technically empowering environment, was were I really got my passion for programming. There is a recurring lesson in those diametrically opposite early experiences: if you put too much administration and crud in the way of actual programming, people loose, or never even gain, a passion for it, for that platform, for that programming language. I see it at the moment for apps in app stores - unless you are aiming for a commercial juggernaut success with an app, the amount of administrative hoops in place, in getting a listing on Google Play or Apples App Store, reminds me very much of the Monash days in the 1970s with too much admin in the way of actual coding. Which of course, is one of the main reasons why the Python language has taken off in recent times, and not because it is a well-designed language, which its not.

Anyway, to cut a long story short, for the sake of this page or two on my 1984 happenings, from 1980 until the start of 1984, I'd carved out a well-considered local reputation in the organisation, mainly as a database expert, on the then new technology called an RDBMS - the Relational DataBase Management System. I'd designed and built the organisations main reporting system, named ARTEMIS - the Australian Road Transport Executive Management Information System - and got a bit of kudos in the process, including a couple of research papers, and a Profile in the dominant Australian Road Research Journal [3,4].

By the start of 1984 it was time for me to go into the CBD (the city centre), to get a new tech role and a big jump in salary for the year, to put our personal travel plans in place for the following year (1985). My wife stayed put at RMIT and I went to a couple of job interviews. The first one I got, was with the State electricity supplier, the SECV - the State Electricity Commission of Victoria. It was headquartered in William St, with about 7,000 people in the building, of the approximate 11,000 employees State wide. They were mainly an IBM MVS system shop, running on an Amdahl mainframe, accessed predominantly via dumb terminals, but a few graphical IBM workstations in the engineering departments, and there were even a few of those new fangled IBM PCs kicking about!

The first job interview was with two people, one was David Knipe, a rising star manager fairly high up, and the second, whose name I can't recall, but he was the 'bad cop' in an apparent 'good cop, bad cop' interview process. That went ok, I thought, and sure enough I got a second round interview, this time with two people in the actual department where the job was located, namely as a Senior Analyst Programmer, in the Forecasting and Tariffs Department. It was a new department, as the SECV had been instructed by the newish Cane Government, to do some 'actual' forecasting of the States energy needs, instead of just using the federal GDP forecast as a rough proxy. Again, it seemed to be a 'good cop, bad cop' interview process. The good cop this time was another David, a Mr. Lukies, a very congenial senior engineer who would be the immediate supervisor, while the 'bad cop' was the manager of the department, a Mr Anderson. Well, this interview didn't go well at all, as I had a standup argument with my would-be department manager! This was very unusual for me, as I generally get along with about 98% of people in a given organisation, but this guy really ruffled my feathers, and me his, apparently. It was about a question he posed as to whether I considered myself to be an Engineer, according to my university qualification, or a Programmer, which was "some lesser endeavour, of which the word 'professional' shouldn't be associated.", was his general drift. This was a time when the Professional Associations of Engineers were proactively considering the idea of placing the letter Eng. in front of a Member's name, much like a doctor uses the prefix Dr, for example, Eng. Anderson instead of Mr. Anderson ;|

I'm afraid I couldn't take that seriously at all, and besides the slight chuckle I couldn't hold back, I said that I definitely sided with the Computer Programmers as my cohort of Professionals, rather than with the Engineers. And from there on it escalated into a standup argument, from which I was happy to leave about 30 minutes in, along with any prospects of working at the SECV! It was apparently a seriously hard-core engineering outfit, through and through, I thought to myself. We had a term for it on the Monash campus - there were small 'e' engineers and capital 'E' engineers. The former had societal and cultural interests beyond just the Engineering.

Well, you could have blown me over with a feather when I received the job offer from the SECV. I couldn’t quite believe it. "That manager must have just set me up", I was thinking - "he really knew how to play his bad cop role in the interview process, I'd fallen for it, you really had to hand it to him!" was my misguided thought at the time. Not so, as it turned out. That guy certainly loved an argument, and apparently I'd proved I could rise to such an occasion, when necessary. It wasn't in the job ad, but clearly, it was this guys main attribute that a candidate should have!

Before taking up the new position at the SECV, a between-jobs opportunity came up, to travel to New Zealand for 4 weeks R & R. This seemed like a good 'test-case' of our ability to travel well in another country for a period of time, given that New Zealand was so much closer to Australia than the EU, not only in distance, but clearly the two cultures were very similar. It was to be with a couple to whom we had both been great friends since high school days, who were budding sailors. Chris had sailed mainly a 14 foot catamaran in the Eildon Weir, a very large freshwater reservoir, between our respective home towns, Alexandra and Mansfield. And he and Sally were preparing to start sailing in an ocean going yacht, like one they would eventually buy, to pursue their own long term travel dreams. So, our first 2 weeks in New Zealand were in the Bay of Islands, on a hired 35 foot sailboat, with a cabin that slept 6 if need be, and full cooking facilities for our daily catch. Chris was the Captain and I was the Navigator (a dual role arrangement that reappeared several times in my IT career), and the other two were more flexible. Did I mentioned there is about 80 islands in the said bay!? The navigation was very manual - charts, rulers, compass and protractor - no digital devices onboard at that point in time, so I was a bit constrained. Anyway, that all went well. We’d driven a hire car up to Opua on the Bay of Island, to board the moored yacht, and I got the short-straw to drive the car back to Whangarei, the nearest car-return point about 70K South! No Uber back then, not even a taxi, so I had to hitchhike back to the others on the boat - a common mode of transport in the 1970s and 80s.

We lived on the daily catch - Chris and Sally were also spearfishing divers, and caught some really good fish and lobsters. The place was teaming with fish. The local indigenous were allowed to net a beach when and wherever they pleased, and each time they did, the nets were weighed down with bucketloads of fish! Hard to starve in the Bay of Islands. We even ventured out of the Bay, and headed up the coast some distance to Whangaroa - in a spectacular inlet, which would be a tourist drawcard in any other country (NZ has such an abundance of scenery), yet there was just one pub for a counter meal, and a few houses there. One thing I did learn, was that sailing a boat then wasn't nearly as technical (digitally) as I would have liked it to be, so that was my last venture at sea in a yacht, as navigator. Whereas our co-sailors, Chris and Sally continued on with many a voyage in the years post-NZ, in a succession of yachts they owned and upgraded. E.g. they came 3rd in the Sydney to Osaka Yacht Race, not too long after. So, us other two landlubbers had been in really good hands, the whole while in the relative pond-like conditions that is the Bay of Islands. That adventure rocket-boosted our travel plans for 1985.

Our other 2 weeks in New Zealand were south of Auckland in a camper van, mainly around the spectacular South Island. The bookings for flights, yacht, and campervan, where all done through travel agents, in-person, or phone and fax - no commercial Internet in those days. Daily travel plans and were day-by-day follow your nose. Apart from the South Island we also took in places like Rotorua and Wellington, the NZ capital, on the North Island. Again, no computers in sight, throughout the journey. I became acutely aware of what computers could do to revolutionise the travel industry - just one of the many areas of human endeavour that 'really needed’ computerisation!

However, that 'back-to-nature' trip san-technology, was appreciated by me over the next 5 months once back at the SECV, where I was doing 10 hour days, on their Amdahl mainframe, with a State Government Budget deadline pushing the forecasting and tariff model hacks (via several programming languages, COBOL, PL1 and SAS***), I was required to do, ultimately for the State Treasury, as the SECV was highly profitable and contributed significantly to the State government budget each year (this was before it was carved up and privatised, in the following years, by the Kennet government). I have an earlier blog article on my SECV experience across the rest of that year, here: https://www.digitalfriend.org/blog/month2020-01.html

Later in the year one of the research papers about my experience building one of the first large Relational DBMS applications, got accepted into the main ACS (Australian Computer Society) conferences, and published in the proceedings [4].

I clearly remember presenting at the Conference, but more so, the conference dinner, which was in the revolving restaurant at the top of Sydney Tower Eye, the tallest structure in Sydney, then and now. As a Speaker I was sitting on a table with Roger Clark, a key organiser of the event and renowned a Australian Computer Professional (I certainly recall his input into the Hawke government's controversial attempt at an Australian ID Card in 1988, which never got up … a story that deserves another blog article). It was the night of a severe storm in Sydney. The view out the window was just fog as we were in the clouds. The lightning flashed and the thunder rumbled on into the night for hours, about one flash per second. I walked back to my hotel later in the evening, through overflowing water halfway up to my knees. My shoes were shot. The city was awash - nothing like the sunny blue sky and scant clothing in the conference brochure! However, the year was near its end, and 1985 was getting very close. My anticipation for a big year-long travel adventure was building.

Steve Goschnick (gosh'at'DigitalFriend.org)

Notes:

*The Fortran language is making something of a come-back these days. E.g. On the Tiobe.com Index of Top Programming Languages, its currently about 12th and still rising up the ladder. It has been modernised here and there, over the years, for example here are the standard versions that came before and after Fortran77: it was developed at IBM by a team of 10 lead by John Backus and released in 1957; an ANSI Standard was developed in 1966 to stop the spread of different dialects, thereafter called Fortran66; the version I first learnt was Fortran77, which gained a Character data type, together with many related string functions which made it highly useful beyond just Science and Mathematic domains, and structured programming support via block IF and block ELSE statements; Fortran90 which notably added Modules to better organise ones code into separately compiled units, 31 character variable names up from a mere 6, recursive procedure calls, pointers, operator overloading, Case statements, and so on; Fortran95 addressed features to improve performance and avoid some problems, e.g. Allocatable arrays instead of promoting pointer arrays; it gained Object-Orientation in Fortran2003, also referred to as Modern Fortran, interoperability with C (and hence, many other languages), sub-modules to hide ones valuable code, access to OS environment variables and commands, i.e. it became a 21st century programming language that year; concurrent programming was added, including coarrays, in Fortran2008 to take better advantage of multi-core chips; the 2018 and 2023 Fortran standards are minor enhancements. Fortran's current rising popularity is most likely due to its efficient matrix computations, very useful for Generative AI number crunching using graphic chipsets such as those from Nvidia.

** A Fortran joke (the necessary backstory: In Fortran77 variable names that started with the letters 'I' through to 'N' were by default Integers, while names that started with the rest of the alphabet were Real): "In Fortran, God is Real."

*** SAS - a Statistical package with its own internal programming language - much like SPSS. SAS is currently up to Version 15, is over 50 years old, and is owned by the SAS Institute Inc. See at https://sas.com. It has been, at various times, the largest privately owned software company in the world (including in 2023), and was one of the fastest growing companies in the US in the 1980s. Its owners are currently targeting an IPO in 2025. It's trying to take its analytic user base into the current Generative AI revolution with "SAS Viya Workbench is intended for building AI models by using programming languages such as Python, R, and SAS. App Factory, on the other hand, can be used for creating AI-based applications" . . . See: https://www.infoworld.com/article/2334798/sas-viya-analytics-suite-gets-saas-based-ai-app-development-tools.html

References: my early research papers in Transport Engineering & Database Systems

- P. Dumble & S.B. Goschnick (1980). Some Improvements to Current Practices of Estimating Individual Choice Models with Existing Data. Proceedings 6th. Australian Transport Research Forum, Brisbane, pp 449-480.

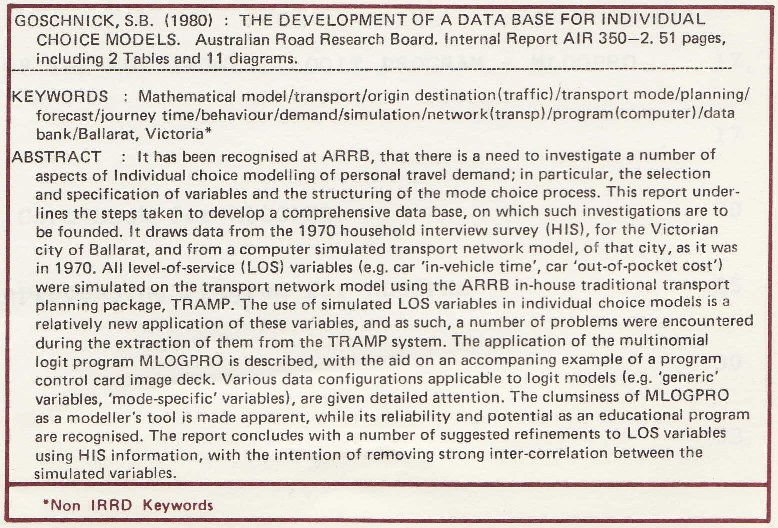

- Goschnick, S.B. (1980). The Development of a Database for Individual Choice Models. Australian Road Research Board, Report AIR 350-2, 51 pages, including 2 tables and 11 diagrams.

- S.B Goschnick (1983). Research in Progress: ARTEMIS – The Application of a Database Management System to Research Project Reporting at ARRB. Australian Road Research, 13(3), September 1983. Pp226-233. [Nb: In Profile, p242, same issue of Australian Road Research].

- S.B. Goschnick (1984). DBMS (Data Base Management Systems) in Research Project Management. Proceedings of the Australian Computing Conference, Sydney, Nov. pp 179-191.